Subject Guide

Mountain West

Malachite’s Big Hole

Canoes:

Travel through the interior of North America would have been more difficult without the canoe, a watercraft perfectly suited to the rivers and lakes of the eastern and northern portions of the continental interior. Indians had always used canoes, and it did not take long for European newcomers to recognize the value of these craft. In the early 1600’s Champlain wrote: "In their canoes the Indians can go without restraint, and quickly, everywhere, in the small as well as the large rivers. So that by using canoes as the Indians do, it will be possible to see all there is."

Canoes were made of birch bark, strong, but light. One person could carry a small bark canoe around the many rapids and waterfalls that blocked the interior rivers. To construct a canoe, the builders peeled bark from the birch trees in long sheets that were then sewn together with roots and attached to a cedar frame. Tree roots were used as thread and the seams between the bark sheets were sealed with spruce or pine resin. One drawback to the bark canoe was its fragility; any sharp rock could easily punch a hole in the side or bottom. However, these canoes could be as easily mended. Paddlers always carried with them a bundle of fresh bark and some pine resin to patch holes.

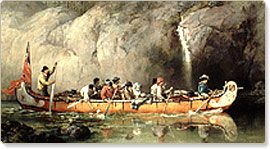

Canoes came in different shapes and sizes. The bark canoes made by Native people for getting around in the woods were quite small and could be carried on the shoulders of a single paddler. Fur traders and explorers required larger canoes for carrying quantities of furs and other cargo. The largest were called canot du maître (Montreal Canoe). These giant craft were up to 36 feet long, carried five tons of cargo and required a crew of as many as fourteen voyageurs to paddle them. They were used to ply the routes between Montreal and the head of Lake Superior. In some cases on big water, they would be equipped with make-shift oarlocks to facilitate rowing.

Canoe sails, some as simple as holding up a blanket or mat, were also used if the

wind was reliable. In the wooded fur country beyond the Great Lakes, the canot du

maître was too big to wrestle around the portages, so traders used the smaller canot

du nord. It was 21 feet long, and carried only half the cargo and crew of the larger

vessel. The canot allège, or Indian canoe was a small vessel 8 to 10 feet in length.

The image to the right is a canot du nord by Francis Hopkins.

Prior to the era of the Mountain Man in the far west, brigade was a term applied to a fleet of canoes. When they were on the move, it was customary for a canoe brigade to rouse itself well before dawn and put in four hours of paddling before pausing for breakfast. The average workday lasted 16 to 18 hours. A bark canoe could be paddled across water at close to six miles per hour. It was exhausting work, but preferable to the portages, where the cargo, carefully packed in 100 pound packs, had to be unloaded and carried on the backs of the voyageurs, along with the canoe. Sometimes these portages were as much as nine miles long, going across swamps and over steep hillsides, and a voyageur would have to tramp back and forth several times to transport the canoe, gear and trade goods and/or furs. While portaging, the voyageurs would be allowed rest stops, usually at about one-half mile intervals. The voyageurs would often be allowed to smoke a pipe at each stop. As a result, portages were often described by the number of pipes allowed. Grand Portage was a 16 pipe portage since it was just over 8 miles long.