Subject Guide

Mountain West

Malachite’s Big Hole

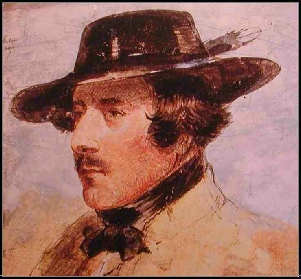

Sir William Drummond Stewart:

Sir William Drummond Stewart is a study in contrasts, a Scottish nobleman wh o came

to North America seeking adventure in the Rocky Mountains, and who subsequently fell

in love with the people, scenery and life. He is a unique mountain men. He spent

parts of seven years living in the western wilderness, performing the duties of a

hunter and brigade captain. In the last years he spent in the west his finances improved,

and with the luxuries he could now afford he became a kind of wilderness prince.

It is through his efforts to preserve something of his experiences and memories

for himself, that we have some of our best images of the Mountain Men of the 1830's.

The picture above was done by Alfred Jacob Miller probably in 1837.

o came

to North America seeking adventure in the Rocky Mountains, and who subsequently fell

in love with the people, scenery and life. He is a unique mountain men. He spent

parts of seven years living in the western wilderness, performing the duties of a

hunter and brigade captain. In the last years he spent in the west his finances improved,

and with the luxuries he could now afford he became a kind of wilderness prince.

It is through his efforts to preserve something of his experiences and memories

for himself, that we have some of our best images of the Mountain Men of the 1830's.

The picture above was done by Alfred Jacob Miller probably in 1837.

William Drummond Stewart was born December 26, 1795 at Murthly Castle, Perthshire, Scotland. His father was Sir George Stewart, 17th Lord of Grandtully, 5th Baronet of Murthly, and his mother was Catherine, eldest daughter of Sir John Drummond of Logiealmond. William was the second of five sons, and two sisters. William never got along with his older brother John, and a deep enmity grew between the two men as they got older.

William was educated at home by tutors. Only the eldest son could inherit the titles and estate, and as second son, it was decided that William would go into the Army. After his seventeenth birthday in 1812, which was the age of military service, William asked his father to buy him a cornetcy, in the elite 6th Dragoon Guards. His appointment was confirmed on April 15, 1813, and he immediately joined his regiment and began a program of rigorous training. Stewart was anxious to participate in military action and on the December 22, 1813 Stewart made an application for an appointment to a lieutenancy in the 15th King's Hussars. The appointment was confirmed on January 6, 1814.

His regiment was almost immediately sent out to take part in the Peninsular War. The war, which started in 1808, was fought principally between England and France, but mostly on the soil of Spain and Portugal. Stewart's regiment arrived in Spain in January 1814. After a winter of extreme hardships, fighting between the French and English armies commenced. Wellington, the English commander, was determined to win victory as quickly as possible, while the French General Soult, was fighting a determined rear-guard action while moving his army back onto French soil. Casualties were heavy on both sides, and Stewart was involved in action numerous times. On April 18, 1814, an agreement to lay down arms was signed after the English had captured the French town of Toulouse.

Almost immediately after conclusion of hostilities, Stewart's unit was returned to Britain, where they were settled in to a routine existence at the Dundalk Barracks in Ireland. Then in March, 1815 intelligence was received that Napoleon had escaped from the Island of Elba and was back in France where Napoleon was again raising an army for European conquest. Immediately, the military might of both England and Prussia was mobilized to end the threat posed by the French forces. By mid-April, 1815, Stewart's unit had arrived in Belgium, and on June 17th the combined armies of the Prussians and British were assembled on the field at Waterloo.

With the French defeat at Waterloo, Stewart's unit was again returned to its barracks at Dundalk. By this time there was also peace with the United States. After some time it must have been apparent to Stewart that there would be a reduction in military forces. On June 15, 1820, Stewart was promoted to a Captain. In October 1821, Stewart's unit, the 15th King's Hussars was disbanded.

Not much is known of Stewart's activities for the next several years, except that he traveled about Europe, and in general lead the life of a fashionable, young man, attending parties, balls, and other court functions.

In 1827 Stewart's father died, and the titles, castle and estates went to John Stewart. William did inherit a sum of £3000, but with the provision that John would control and manage the money. William was of course outraged, especially when John did everything possible to delay, minimize, or simply not disburse any funds at all from the inheritance to William.

For the next few years William had sufficient funds to cover basic expenses, but not enough to travel or live in the style which he wanted. Much of this period was spent on the London social scene, or staying with friends of the family.

Some time in 1829 William met an extraordinarily beautiful young woman, a maid, named Christina Stewart (no relation), with whom he fell in love. In 1830, Christina bore William a son, George. Though there was no marriage, William freely acknowledge the boy as his. Three months after the birth, William and Christina were married in Edinburgh. Although the marriage was not secret, the two never occupied the same home, she living in an apartment in Edinburgh.

Some time in 1832 William had a huge fight with his brother John. In the time following the quarrel, William determined to escape the London social scene and the confines of family by travel and adventure. He was attracted by North America and the Far West. The promise of wild vistas, struggle and danger in the Western wilderness held an appeal to a basic part of his character. An added advantage of travel in the wilderness and frontier was that the costs would be far lower than in the European capitols, where he would have to maintain the standards of his class.

His plans were hazy at best. He obtained letters of introduction to several senior Hudson's Bay Company men in Canada. His plans did include several months in New York City, New Orleans and thence to St. Louis. From there, somehow he would find a way to the mountains. He took with him a wardrobe of elegant clothing for socializing in New York and New Orleans, and two Manton hunting rifles, costly weapons, and amongst the finest firearms crafted at that time.

Stewart had been in New York City only a few days when he met J. Watson Webb, a prominent individual in the community. Webb had ten years of army experience on the frontier, and was three years a newspaper editor. The two men formed a friendship that lasted for years. Through Webb, Stewart would receive additional letters of introduction to William Clark (Lewis and Clark) then Superintendent of Indian Affairs, William Ashley, originator of the mountain rendezvous, and William Sublette and Robert Campbell, outfitters and suppliers for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

Webb strongly advised against travel to New Orleans. New Orleans was in the grip of a cholera epidemic, a disease which was frequently fatal. Shipping most of his baggage by boat, Stewart chose to travel by horse overland through Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and into Missouri. Within a few days of his arrival, he called on Clark, Sublette and Campbell. During the winter of 1832-1833 he would form lasting friendships with all three men.

Late in the winter of 1833 Campbell and Sublette were preparing goods and supplies for the mountains. That year Campbell was to lead the pack train to the 1833 Rendezvous, somewhere on the Green River, and Sublette was to transport goods and supplies, first by steamship, and then by keelboat upriver as far as the Yellowstone. As Sublette and Campbell's preparations progressed, Stewart decided to accompany Campbell with the supply train. At Stewart's own insistence, he would be a paying guest, laying out $500 for the privilege of accompanying the train.

Stewart was not the only paying guest that year. Benjamin Harrison, son of William Henry Harrison (eventually ninth president of the United States) would pay $1,000 to accompany the supply train. In those times, a trip to the Rocky Mountains and West was considered to be a near sure-cure for most deficiencies of character and ailments from alcoholism to tuberculosis. Harrison was given to frequent excessive indulgence to strong drink, a malady which was characteristic of the culture and society of the time (more about Alcohol in Society)

In the weeks prior to the departure of the supply train for the mountains, a scientist/traveler, Prince Maximillian and his party consisting of one servant and an artist of some fame, Charles Bodmer arrived in St. Louis. Prince Maximillian wanted to travel with a caravan into the Indian country to study the natives as well as collect plant specimens. After some discussion with Robert Campbell, Prince Maximillian decided that it would be safer to travel by steamship. Soon thereafter he and his party left on the Steamship Yellow Stone.

On May 7, 1833, Campbell's supply train set off from Lexington. The brigade was made up of 43 men, including Robert Campbell, Louis Vasquez to look after the train, Basil Lajeunesse to bring up the rear and take care of stragglers, Stewart, Benjamin Harrison and Edmond Christy, who at the 1833 Rendezvous, would provide financing and become a partner in the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. Charles Larpenteur was a clerk with this supply train an provides an excellent description in his memoirs (Forty Years a Fur Trader). There were approximately three mules per man, one to ride, the others for pack animals. Twenty sheep were driven along to provide fresh meat until the train reached buffalo country.

Benjamin Harrison seemed to be content with his status as paying guest, and assumed no responsibilities, not even for picketing his own animals. Stewart on the other hand had to savor the experience to its fullest and accepted every duty that came his way, from ranging with the hunters to helping Vasquez and Lajeunesse as they struggled to keep order in the train. It was not long before Campbell appointed Stewart as captain of the night guard, because of his intelligence and military experience.

On the morning of the last day of travel, the start was delayed by several hours while the men cleaned up their appearance in anticipation of reunions at the rendezvous. Stewart dressed himself in clothing that had been sealed and none had seen before. He wore a white leather hunting jacket, and a pair of snug trousers known in Scotland as trews. The trousers were of the Stewart family hunting plaid, consisting green, royal blue, red and yellow, fashioned by a London tailor. Stewart's fashionable dress would cause much astonishment and amusement amongst both the white trappers and Indians.

Robert Campbell's supply train arrived at rendezvous on July 5th, three days ahead of the American Fur Company supply train head by Andrew Dripps and Lucien Fontenelle. Captain Bonneville arrived at rendezvous on July 12 with about 110 men, and 300 horses. While at this rendezvous, Stewart would have had the opportunity to meet many mountain men including Thomas Fitzpatrick, Lucien Fontenelle, Andrew Drips, Captain Bonneville, Michael Silvestre Cerré, Joe Walker and Joe Meek. He would also meet a hunter, Antoine Clement, who would eventually become a close friend and traveling companion (Picture of Antoine Clement).

On July 24th, after the break-up of Rendezvous, Campbell along with a brigade which included Stewart, Fitzpatrick, Charles Larpenteur, Antoine Clement, Benjamin Harrison, and about twenty trappers, headed north to the Big Horn River, and thence down to the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers. Campbell was to meet William Sublette with the keelboats that Sublette's brigade had dragged up the River to that location earlier in the year. At the last moment, Nathaniel Wyeth, Milton Sublette and their small party joined with Campbell. Once the men reached the Big Horn River, bull boats were constructed to transport the furs down river.

Fitzpatrick and the twenty trappers, along with Stewart remained behind, intending to hunt and trap in Crow Indian country. The Crow Indians proved to be unfriendly towards Fitzpatrick's brigade, and after an incident in which the trappers lost much of their equipment, and many horses, Fitzpatrick's brigade left the country.

There is no record as to how Stewart spent the winter of 1833-34. There are no reports of Stewart in either St. Louis or New Orleans during this time. The first reliable report of Stewart in 1834 has him in the company of Jim Bridger heading to the 1834 Ham's Fork Rendezvous. It is quite possible Stewart wintered in the mountains. Both men arrived at rendezvous during the second week of June.

On June 18th, William Sublette, who was leading the supply train this year, arrived on site. Three days later, Nathaniel Wyeth, who had a supposedly secret arrangement to supply the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, arrived. It was too late, Sublette and Campbell had already called in debts owed them by the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and forced the company to dissolve. For Stewart, the rendezvous was an opportunity to renew old friendships and make new friends.

Wyeth, greatly disappointed with the results of the rendezvous, left early. Wyeth planned to continue on to the Lower Columbia River Basin where he had additional business and commercial interests to attend to. Stewart, in search of new adventures, accompanied Wyeth, as did a party of missionaries and two scientists, Nuttall and Townsend.

About July 12, 1834, the brigade reach the confluence of the Snake and Portneuf Rivers. At this location Wyeth had already decided, from previous travels through the area, to construct a Fort Hall. On August 4th, the fort was largely completed. Leaving twelve men behind at the fort, Wyeth, still accompanied by Stewart, set off on August 6th with the remaining men for the Lower Columbia.

Wyeth's brigade continued to travel by horse until they reached Fort Walla Walla, situated on the Columbia River. Fort Walla Walla was an important post belonging to the Hudson's Bay Company. Here they disposed of their horses, and transferred their remaining goods and supplies to pirogues for the final leg of their trip down to Fort Vancouver, where they arrived September 16, 1834.

Fort Vancouver's Chief Factor, Dr. John McLoughlin warmly and generously received Wyeth, Stewart, the missionaries and scientists. What Stewart did for the remainder of the fall and winter of 1834-35 is not recorded. It's probable that he spent time traveling in the area and visiting the settlement of Jason Lee in the Williamette Valley. It is inconceivable that he traveled this far across the continent without pushing on to see the Pacific Coast.

On February 11 1835, Stewart accompanied a small party of men under Francis Ermatinger, taking large pirogues loaded with supplies for the upriver posts. The party was probably engaged in trapping as well as transporting supplies, because it took them until June 10th to reach Wyeth's Fort Hall. Here they outfitted with fresh horses, and traveled on to the 1835 Rendezvous, arriving around June 20. This was much too early for the expected supply trains, but there was much to do in the meantime as trappers and Indians began arriving over time.

Lucien Fontenelle, was leading an American Fur Company supply train to this years rendezvous. The supply train was accompanied by two missionaries, Dr. Marcus Whitman and Samuel Parker who were assessing the prospects for establishing missions amongst the Indians in the west. The supply train was extremely late arriving at rendezvous this year. Part of the reason may have been an attack of cholera which hit the men as they were passing through Bellevue. Most of the men were stricken, including Fontenelle. Two men died, and in twelve days the disease had largely run it's course.

When the train arrived at Fort William on July 27th Fontenelle was still so weak from his experience with the cholera that he remained at the fort, allowing Fitzpatrick to guide the train the remainder of the way. The supply train wouldn't arrive at rendezvous until August 12, so late that most of the trappers and Indians at rendezvous were in despair of receiving needed goods and supplies.

While at rendezvous Stewart probably received one or more letters from New Orleans suggesting certain business arrangements that would be advantageous to himself as well as letters from home. Stewart probably spent much time with Marcus Whitman and Samuel Parker, who were very interested in conditions on the Columbia River and in the Fort Walla Walla area. The mission possibilities seemed so favorable that Parker and Whitman decided to split. Parker would travel on to examine the area around Fort Walla Walla, and then go on to Jason Lee's settlement on the Williamette. Whitman would return east to recruit more missionaries and solicit additional financial support.

Thomas Fitzpatrick packed up the accumulated furs on August 27, 1835 to return to St. Louis. Traveling with Fitzpatrick was Marcus Whitman, Stewart and his friend Antoine Clement. Clement would stay with the train until it reached Bellevue where he would turn back towards the mountains. Stewart continued on to St. Louis. At this time he had been in the far west for three summers and two winters, living the same lifestyle as any mountain man.

When he arrived in St. Louis there were additional letters from home, as well as a partial payment of his annuity from John Stewart. He must have had some time to reflect that life would be much easier given enough money, even life in the wilderness. Within a few weeks he traveled to New Orleans to pursue the business opportunities. He became involved as a business agent involved in purchasing raw cotton fiber for the cotton mills that were then so important to the economy of England. He also became involved in a business partnership with the British Consul in New Orleans. The purpose of this business is unknown, but was sufficiently involved to hire a representative in London for several years.

With the proceeds of these two ventures, Stewarts financial outlook suddenly improved. Towards the end of the winter he was able to travel to Cuba and then on to the southeastern United States.

Stewart still planned on returning to the mountains for the Rendezvous of 1836 and he wrote to William Sublette to obtain certain supplies and horses in preparation for this. Stewart would travel to the mountains this year in style, filling two wagons with luxury goods such as canned meats and sardines, plum pudding, preserved fruits, coffee, fine tobacco, cheeses, and a selection of brandies, whisky and wines. He also had three servants, two dogs, and two running horses.

Dr. Marcus Whitman, his new wife Narcissa, and a party of missionaries and lay people arrived prior to the departure of the supply train, intending to accompany the train as far as rendezvous. The supply train left Bellevue on May 14, 1836, under the leadership of Thomas Fitzpatrick, accompanied by Milton Sublette and arrived at rendezvous on July 6, 1836.

While the business of exchanging furs for goods and supplies was ongoing, Stewart, some friends and his servants disappeared from the scene. Based on Stewart's fictional story, Edward Warren, it seems probable that his party traveled up into the Wind River Range for a private hunting expedition. At some point Stewart's party met up with a small party of trappers lead by Jim Bridger. Together the combined group traveled to Fort William where they rejoined Fitzpatrick's pack train, now headed for St. Louis with the years accumulation of furs.

On his arrival back in St. Louis he again received a packet of letters from his family in England. At least one or more these letters contained the news that his older brother John had contracted some fatal disease. Because John had no children, there was a reasonable expectation that William Stewart would eventually inherit the title and estates. Stewart must have started making plans for this eventuality. Some of these plans included taking as much of the West that he loved back to Scotland when he should return.

During the winter of 1836-37, Stewart spent much time socializing in both St. Louis and New Orleans. He also spent time attending to his different business ventures. In April of he engaged Alfred Jacob Miller, an artist to accompany him with the supply train to the 1837 Rendezvous. Miller was to make sketches and drawings of the scenery, people and events. The drawings and sketches would eventually be transformed to paintings which would adorn Stewart's castle in Scotland. Historically Millers paintings and drawings are invaluable, preserving scenes from a way of life which was even then rapidly disappearing.

During the preceding year, John Jacob Astor had sold his interests in the American Fur Company. The Western Department was sold to Pratte, Chouteau and Company. The company was still commonly known as the American Fur Company. The company was planning to send a supply train up to the 1837 Rendezvous, and Thomas Fitzpatrick, a long time friend of Stewart was to lead the train. Stewart would accompany Fitzpatrick, but was planning on taking his own private outfit. The outfit would consist of ten men, Stewart, Miller, Antoine Clement, Francois Lajeunesse, a cook, three engages. and two packers. Stewart again planned to travel in style with an assortment of luxury foods, wines and liquors.

The supply train probably arrived in early July, and by July 20th was starting to break up. Stewart secretly brought out a steel cuirass and helmet of the Life Guards, an elite British military outfit. While at rendezvous Stewart presented the armor to Jim Bridger. This gift was undoubtedly the culmination of some long standing joke between the two men, as there was no need or use for such an item in the Rocky Mountains. Alfred Jacob Miller painted two sketches of Bridger wearing this outfit.

At the conclusion of Rendezvous, Stewart again took a private hunting trip of about ten days duration up into the Wind River Range. The group probably totaled about twelve men. They camped several days by a large lake they called Stewart Lake. This lake was later "discovered" by John Fremont and renamed Fremont Lake. By mid-August it was time to start heading back, but not before one more swift trip through the wilderness. Details are scarce, but it seems that Stewart's party headed to the Big Horn, across to the Yellowstone River, then turning west to the Rosebud and Cross Creek. Thence the party went down into the Teton Mountains. From there the party headed eastward to Fort William where they caught up with the supply train loaded with furs bound for St. Louis. Stewart, Miller and Antoine Clement returned with the train arriving in St. Louis in mid-October. Miller immediately returned to New Orleans to begin working on paintings. Stewart remained in St Louis for several months before moving down to New Orleans where he spent the remainder of the winter attending to his business affairs.

In March 1838 Stewart returned by steamship to St Louis, where he again prepared to attend rendezvous. Pratte, Chouteau & Company, (formerly the Western Department of the old American Fur Company) would take a supply train to the 1838 Rendezvous under the leadership of Andrew Drips. Stewart and Antoine Clement assisted Drips with the train. The location of rendezvous was to be changed to the Wind River, saving more than 100 miles of travel for the supply train (Map). This was done both for economy and to discomfit the Hudson's Bay Company, which was becoming an ever more aggressive competitor at rendezvous. Stewart, although still traveling in style, only took one wagon with his luxury goods to this years rendezvous.

The train left Westport sometime in early April and arrived at Fort William on May 30. Several days were set aside for rest, repair and recruiting before setting off again. On June 23, 1838 the supply train arrived at the rendezvous site, at the confluence of the Popo Agie and Wind Rivers. Because of both the change in location, and structural changes in the fur trade, this years rendezvous would be less well attended than those in the past, but it was still the social and commercial event of the year. This would be the last rendezvous that William Stewart would attend and he was no doubt busy socializing with his many friends made over the years.

Sometime in July the rendezvous began to break up. As in previous years, Stewart and a small party went off for a private hunting trip up into the Wind River Range. By early August the party was making its way down to the Platte River and then on down the Missouri River. Somewhere along the way, Stewart received the news that his brother John had died on May 20.

After arrival in St. Louis, Stewart spent several months in correspondence, organizing his affairs and planning for his new future. He then traveled on to New Orleans to continue his business affairs there and to see how Alfred Jacob Miller was progressing on the paintings. In April Stewart returned again to St. Louis, this time to gather up mementos of his time in the far West. In addition to artifacts and cultural items, he would also take seeds, birds, and two buffalos and a young grizzly bear. He even took two Indians. When Stewart finally left St. Louis for New York later in April, he informed William Sublette that he would be returning in 1840 for another trip to the Rocky Mountains. Stewart finally left for Perthshire on May 25, 1839. With him went Antoine Clement and the two Indians. Alfred Jacob Miller would travel to Scotland the following year to complete his paintings made in the far West.

Stewart's affairs in Scotland required far more time and effort than he ever imagined, and he was unable to return to the West in 1840. Alfred Jacob Miller finished up his work for Stewart and returned to the United States in February of 1842. At the time they parted, Stewart assured Miller that they would meet again in the fall of 1842.

In August of 1842, Stewart, again accompanied by Antoine Clement and the two Indians sailed for the United States, arriving in New York on September 7. He spent some time in New York socializing and corresponding with friends before he traveled on to Baltimore. Here he met with Miller, commissioning the artist to paint two more pictures for his estate. From here he traveled on to New Orleans arriving in November. Antoine and the two Indians were sent on ahead to St Louis.

The last of the great summer rendezvous had been held in 1840. Structural changes in the fur trade, and the steam ship revolution in transportation made it far more economical to support a far flung network of posts and forts along the Missouri River and it’s major tributaries.

However, for the summer of 1843 William Stewart was planning a private, by-invitation-only rendezvous, or "hunting frolic" in the Wind River Range. This trip would bear only a faint resemblance to the trips with the supply trains that he had accompanied in earlier years. Instead of being driven by competition, economics and the hard considerations of dollars and cents, this would be a trip of pleasure, fun and adventure. With a few notable exceptions, the men he planned to take with him were young, and inexperienced in the ways of the mountain. He planned to run the trip under a form of military discipline, but he also planned on having available all those luxuries which could be transported to the wilderness. In a way the objectives of the trip could not help but foment personal conflicts and conflict did result.

Familiar figures who accompanied Stewart on this trip include William Sublette and Antoine Clement. Baptiste Charboneau (of Lewis and Clark) was hired on as a driver. Four European botanists; Dr. Mersch, Friederich Luders; Charles Geyer and Alexander Gordon and an American Physician, Dr Steadman Tilghman were also invited to accompany the group. Also, a group of Catholic Missionaries received approval to accompany the party as far west as the Rocky Mountains. The young gentlemen invited to accompany the frolic numbered about thirty, some who also took servants along. Finally there were thirty or thirty-five hired hands to cook, tend to the horses, and all the other necessary chores. Of the "young gentlement" William Sublette wrote in his journal, "Some of the armey. Some professional gentlemen. Some on a trip for pleasure. Some for health, etc., etc. So we have Doctors, Lawyers, botanists, Bugg Ketchers, Hunters and men of nearly all professions, etc., etc."

Sometime during the last week in May, Stewart's party headed out across the prairies, back to the Rocky Mountains that he loved so much. The young, and inexperienced men had much to learn, and conditions that were just "part of a day" for the mule skinners in the supply trains of previous years, presented real hardships to some of these men. So to the military discipline that Stewart kept the group under caused friction and resentment at times. By the first part of August the group had reached Stewart's Lake in the Wind River Range where they were joined by a group of thirty to forty Shoshone Indians.

The group remained encamped until mid-August, feasting, hunting and gambling amongst themselves and with the Indians. On August 16, camp was raised and the party began it's long trek home. On the return trip, the same frictions and resentments arose, only made more urgent by the desire of the homesick? young men to make haste. Sometime in the later part of September the group split into those that chose to stay with Stewart, and those who couldn't delay any longer and left in a "high dudgeon." Both parties traveled on with no great distance separating them. Even though traveling separately now, members of each group still visited back and forth. The rebel group arrived in St. Louis a couple of days ahead of Stewart's party. By this time all of the differences seem to have been forgotten, and one of the members said afterward in St. Louis that "amidst much good fellowship the whole party disbanded."

A few weeks later William Stewart was back in New Orleans where he started a leisurely journey back to Scotland and a far different life than what he had lived in the Rocky Mountains. The remainder of his life was spent managing the affairs of his estate, entertaining, and feuding with various surviving members of his family.

Stewart died of pneumonia on April 28, 1871 at the age of 75.

For more information about William Drummond Stewart see the following:

Porter, Mae Reed and Odessa Davenport. Scotsman in Buckskin, Sir William Drummond Stewart and the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade; published by Hastings House, New York, 1963. A good summary biography of Sir William Drummond Stewart, the Scottish Noblemen who sought adventure in the Rocky Mountains between the years 1833 and 1839. The main problem with the book is it portrays numerous myths as fact (various of the mountain men are described as carrying Hawken rifles and Green River Knives in 1833, long before these were available, and Green River Knives are stated to be manufactured in Sheffield, England) The presence of these myths and errors makes much of the background information suspect and with a lack of footnotes it is difficult to verify information.

Back to the Top

Back to The Men