Subject Guide

Mountain West

Malachite’s Big Hole

Moses "Black" Harris:

Almost nothing is known of Moses “Black” Harris prior to his entry into the fur trade. Based on an interview with Harris published in the St. Louis Democrat on June 12, 1844 , Harris was probably a native of Union County, South Carolina. The nickname “Black” was given to Harris because of the dark coloration of his skin. Alfred Jacob Miller (reference) observed in 1837 that Harris “was wiry of frame, made up of bone and muscle with a face composed of tan leather and whipcord finished up with a peculiar blue black tint, as if gun powder had been burnt into his face." Harris was famous as a man of “great leg” able to walk great distances alone and for extended periods (James Beckwourth reference).

Numerous times Harris made winter treks out of the mountains to St. Louis carrying dispatches and other communications. Indeed, throughout what we know of Moses “Black” Harris' life, he never seemed able to settle down for any length of time, seeming to prefer to be in continual motion back and forth across the west.

Harris probably was a member of William Ashley’s first brigade to the mountains in 1822. In 1823 Harris accompanied Ashley’s second expedition up the Missouri River to the mountains. Passing the Arikara villages was always difficult and this year it would prove disastrous for Ashley.

On June 1, 1823 Ashley along with Jedediah Smith, James Clyman, Moses "Black" Harris and others fought in a ruinous engagement on the beach below the fortified Arikara Indian village. The trappers were routed with great loss of life.

It is likely that Harris was a member of the "Missouri Legion" a mixed force of military regulars, trappers from Ashley's and Pilcher's outfits, and Sioux Indians, all under the nominal command of Colonel Leavenworth. Leavenworth returned with this force to attack the Arikara village in an abortive campaign to chastise the Indians late in the summer.

After the Indians were dispersed (though hardly chastised), Ashley equipped his men with horses so that they could proceed overland to the mountains rather than following the river. The expedition was split into two brigades, one under Jedediah Smith proceeding to the Crow Indian country, the other under Colonel Henry returning to resupply Henry’s established post at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers.

Harris apparently accompanied Henry’s brigade. In December 1823 Harris along with two other men were sent down to report to Colonel Leavenworth at Fort Atkinson of the unsettled and dangerous conditions existing for the trappers on the upper Missouri River country, mainly from the Blackfoot Indians. Harris continued on to St. Louis where he reported to the Missouri Intelligencer that seven members of Henry’s party had been killed by the Blackfeet, several horses had been stolen, and that desertions by the men were common.

Late in 1825 Jedediah Smith, and a party including Harris, left for the mountains with supplies for Ashley’s trappers who were wintering over in the mountains. Bad weather had stalled the brigade, food was running low and the horses were dying. Rations for the men were reduced to one cup of flour per day. The situation worsened when the men couldn’t find a village of Loup Pawnee who they were counting on to obtain supplies and fresh horses.

Harris and Jim Beckwourth were sent back to St. Louis to report the need for more horses to Ashley. Ashley returned the following spring, and the combined parties continued on to the mountains. Ashley sent Smith and Harris on ahead to inform the company trappers in the mountains that supplies were on the way, and that the summer rendezvous would be held in Cache Valley (1825 Rendezvous).

Before the supply train reached the rendezvous, a small party of four trappers circumnavigated the Great Salt Lake by boat, searching unsuccessfully for the elusive Buenaventura River. Harris is believed to have been one of the four men in this party.

By 1824 Jim Beckwourth (reference) states that Moses Harris was an “old and experienced mountaineer” and that Ashley “reposed the strictest confidence for his knowledge of the country and his familiarity with Indian life.”

William Ashley soon had enough of the uncertainties of fur trade and hardships of life in the mountains. At the 1826 Rendezvous Ashley sold out his interests in the company to Jedediah Smith, David Jackson, and William Sublette, the new company being known as the Smith, Jackson and Sublette. At the breakup of rendezvous, the three partners each took out a separate brigade of trappers out for the fall hunt. Harris apparently accompanied Sublette’s brigade.

It was at this time that Sublette’s brigade passed through the area now included in Yellowstone Park, and observed the geysers, mudpots, and petrified forests in the area. Based on his observations, Harris stretched and embellished the truth till he had established his reputation as a storyteller.

George Ruxton (reference) says “…and the darndest liar was Black Harris-for lies tumbled out of his mouth like boudins out of a buffler’s stomach. He was the child as saw the putrified forest…” To read Harris' tale about the "Putrified Forest follow this link.

In selling the company to Smith, Jackson and Sublette, Ashley had agreed that he would outfit and lead a supply train to the mountains in 1827 providing the partners would send him a dispatch prior to March 1. William Sublette and Black Harris left the Salt Lake Valley on January 1, 1827 with the order for supplies. Because of deep snows the men traveled on foot with snowshoes, accompanied by an Indian trained pack dog. The men each carried packs of dried buffalo meat, and the dog was loaded with 50 pounds of sugar, coffee, and other supplies.

While enroute, the men endured severe snowstorms and sub-zero temperatures. Eventually, with starvation looming, the men killed and ate the dog. They arrived in St. Louis on March 4, 1827.

Although there is no documentation of his whereabouts for the next several years, it is likely that Harris returned to the mountains with the supply train bound for the 1827 Rendezvous.

Harris next appears in the records during the winter of 1829-1830 in a brigade of trappers under Jedediah Smith and William Sublette. The brigade had been bogged down by conditions of deep snow in the mountains. Food was scarce and as many as 100 pack animals were lost (Joe Meek, reference). Smith’s brigade eventually forced their way down to the plains of the Big Horn River where they united with another brigade of about 40 trappers lead by Milton Sublette.

The combined parties cached their furs and continued on to the Wind River Valley where they established their winter encampment about Christmas. On Christmas Day, William Sublette, again accompanied by Moses Harris, set out for St. Louis with an order for supplies and goods from Ashley. The men once more traveled on foot, accompanied by a dog team which hauled their supplies and belongings. The two men had learned much about winter travel since their previous trip in 1827, and made good time, reaching St. Louis by February 11, 1830.

Harris drops from view for several years, but he probably accompanied the supply train up the 1830 Rendezvous. At rendezvous in 1830, Smith, Jackson and Sublette sold out their interest in the company to Thomas Fitzpatrick, James Bridger, Milton Sublette, Henry Fraeb and Jean Gervais, a partnership which was then known as the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

It is unknown as to whether Harris didn’t care for the change in management, or if there was another reason, but Harris chose to end his association with the company. During the 1831-32 season Harris worked for the Upper Missouri Outfit (American Fur Company) as a trapper out of Fort Union.

He and a small party were present at the Green River Rendezvous in 1833. His party’s horses had all been stolen by Arikara Indians and the men came in on foot, lugging seven packs of beaver furs. Subsequent to selling out to the partners in the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, William Sublette and Robert Campbell formed a partnership to procure supplies and trade goods and to outfit pack trains to supply the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in the mountains.

In 1834 Harris was one of the men with Sublette taking a supply train to the mountains. The caravan stopped at the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte Rivers, where Sublette left behind a contingent of men and supplies to establish Fort William (Laramie). While at rendezvous, Sublette called in debts owed by the Rocky Mountain Fur Company to Sublette and Campbell, forcing the Rocky Mountain Fur Company to dissolve.

The rendezvous' continued to be held, however, the mountain trade was now dominated by the American Fur Company and its affiliated organizations. In 1836 Harris was acting as guide for the supply train going to rendezvous under the leadership of Thomas Fitzpatrick (1836 Rendezvous). The Whitman-Spalding missionary party accompanied this supply caravan as far as the rendezvous, before heading further west to the Oregon Country in the protective presence of Hudson Bay Company men.

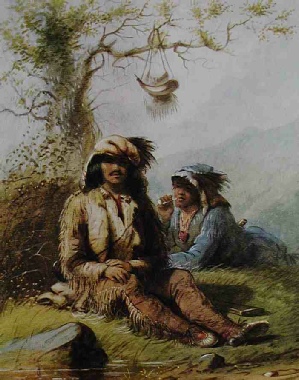

Fitzpatrick and Harris again lead the supply caravan to the Horse Creek Rendezvous

in 1837. Sir William Drummond Stewart, who had been a part of the rendezvous scene

since 1833, was present again at the 1837 Rendezvous. However, this year he brought

along an artist to help preserve the scenes of mountain life. Alfred Jacob Miller,

an American artist who had studied in Europe, made hundreds of sketches of Indians,

mountain men, encampments, hunting and other every day activities, including a drawing

of Moses Black Harris, entitled Trappers. At right is Miller's drawing. Harris

is believed to be the man shown sitting upright.

rendezvous scene

since 1833, was present again at the 1837 Rendezvous. However, this year he brought

along an artist to help preserve the scenes of mountain life. Alfred Jacob Miller,

an American artist who had studied in Europe, made hundreds of sketches of Indians,

mountain men, encampments, hunting and other every day activities, including a drawing

of Moses Black Harris, entitled Trappers. At right is Miller's drawing. Harris

is believed to be the man shown sitting upright.

1838 was the year of the “secret” rendezvous (1838 Rendezvous). The business environment in the mountains had become increasingly cut-throat, and the American Fur Company decided to keep the location of the rendezvous as quiet as possible in hopes that the Hudson’s Bay Company would fail to appear. Of course word of the location had to be spread, or the hunters, trappers and Indians wouldn’t have known where to assemble. The ploy wasn’t successful as a brigade of Hudson’s Bay Company under Francis Ermatinger also arrived on time and location for the rendezvous.

Andrew Drips was leader of the supply caravan this year with Harris again acting as guide. The caravan also included another party of missionary couples, the Grays, Eells, Walkers, and Smiths.

A more fractious group of people purporting to share a goal would be hard to imagine. The individuals and couples of the missionary party, by turns hated and quarreled with each other, but were united only in their disgust for the unspeakable and appalling sin they were forced to witness and even participate in. Imagine being forced to travel on a Sunday! Andrew Drips at one point offered (threatened) to leave the missionaries behind, however, even they had enough sense to realize their chances of survival were slim without the protection provided by the supply train.

The caravan arrived at Fort William (Laramie) on June 2, 1838. Shortly thereafter, Drips sent Harris on ahead to spread word of the location of the rendezvous. At a rundown log structure at the site of the Green River rendezvous Harris posted a note scrawled in charcoal on the door. The note read “Come on to the Popoasia, plenty of whisky and white women.” The note demonstrates a definite sense of humor on the part of Harris, because at this time he well knew from traveling with the missionaries that any trapper expecting to have a good time, friendly conversation, or to even receive a warm greeting and smile from this particular group of white women was likely to be greatly disappointed.

By 1839 the trade in beaver pelts had drastically declined, both in number and value. Harris was in charge of leading the supply caravan to rendezvous this year (1839 Rendezvous). Because of the decline in the trade, the caravan was small, consisting of only four two-wheeled carts, each carrying 800-900 pounds of goods. A German tourist, Dr. Frederick Wislizenus (reference), traveled along with the caravan to rendezvous. In his account of the trip he described Harris as “a mountaineer without special education, but with five good senses, that he well knew how to use.” At rendezvous Wislizenus further describes the kinds of trade goods, prices, living conditions, and leisure distractions available to the mountain men.

In 1840 Andrew Drips lead another small supply train to rendezvous (1840 Rendezvous). This year would be the last of the mountain rendezvous. Missionaries, including Father De Smet, again accompanied the pack train, with the ultimate goal of the Oregon Country. Harris offered to guide the missionaries from the rendezvous site to as far as Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Hall. It’s not known what his charge was to be, but the missionaries considered his price to high. Instead they hired Robert “Doc” Newell. Apparently Harris considered this interfering in business negotiations and he took a shot at Newell with his rifle but missed.

With the decline of the trade in beaver fur and the end of the rendezvous system, Harris chose to utilize his knowledge of the mountains and west as a guide to emigrant trains heading to Oregon. In 1844, Harris guided west one of the largest immigrant companies formed in that year. James Clyman, who was also part of Ashley’s company in the mid 1820's, and who also must have known Harris since that time, was traveling the Oregon Trail that summer. Of Harris, Clyman notes “all of us seated ourselves around our camp fire and listened to the hair-breadth escapes of Mr. Harris and other Mountaineers.” (Reference)

Harris spent the next couple of years in Oregon at times searching for a wagon friendly route through the Cascade Mountains, and at other times rescuing immigrant parties. In 1847 he returned to Missouri and to guiding immigrant companies west.

In the spring of 1849 he had accepted a contracted as guide with an immigrant party and had lead them as far west as Independence, Missouri. While at Independence he contracted cholera, and within a few hours died. A description of his passing appeared in the Independence Daily Union on May 14th authored by “Gerald.” “Within the last 24 hours I have seen the eyes close in death, of three individuals at the hotel ….all victims of cholera, after but a few hours warning. The first was “Black Harris,” the well known mountain guide. He had been chosen to lead us across the Rocky Mountains , but poor fellow, he goes before us on another journey. He seemed to every one who knew him to be a “bird alone” in the wild world, without “kith or kin” to care for or leave behind, to lament his death. But in [his] last moments he whispered to a bystander that away in the mountain fastnesses, far from the haunts of any other white man, among some unknown tribe of Indians, he had a wife and two children, the only objects on earth for which he could desire to live. He would communicate nothing further on the subject, only the request to spread the news as we passed on, that Black Harris was dead and his family would soon learn his fate. Thus it appears the life of this simple mountaineer like that of other men if it were but known was chequered by its share of unchronicled romance.” There is no other indication that Harris had a wife or family.

For more information about Moses “Black” Harris see:The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, Volume IV; edited by LeRoy R Hafen

Back to the Top

Back to The Men