Subject Guide

Mountain West

Malachite’s Big Hole

Dogs:

Dogs played a minor, although at times critical role in the life of a trapper. Dogs

were a ubiquitous part of Indian village life. Numerous descriptions (Kurz, Garrard)

of these animals indicates that they bore a strong resemblance to wolves, both in

appearance and behaviour. Rudolph Kurz describes these dogs as follows: "Indian

dogs differ very slightly from wolves, howl like them, do not bark, and not infrequently

mate with them. Dogs of another type are brought here from the Rocky Mountains -

small, lop-eared canines, covered from head to toes and tail with long shaggy hair."

Although most of the Indian dogs may have resembled wolves, line drawings made by

Kurz

wolves, howl like them, do not bark, and not infrequently

mate with them. Dogs of another type are brought here from the Rocky Mountains -

small, lop-eared canines, covered from head to toes and tail with long shaggy hair."

Although most of the Indian dogs may have resembled wolves, line drawings made by

Kurz  depict at least some blunt-muzzle, relatively shorter haired dogs while he was

employed at Fort Union. These drawings are from Kurz’ journal. Lewis Garrard (Reference)

describes the use of dogs by Cheyenne Indians when moving a village location in 1847:

"Many of the largest dogs were packed with a small quantity of meat, or something

not easily injured. They look queerly, trotting industriously under their burdens;

and judging from a small stock of canine physiological information, not a little

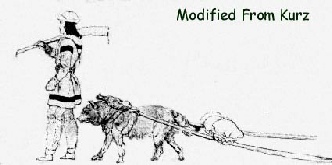

of the wolf was in their composition." The image to below is modified from a drawing

made by Alfred Jacob Miller in 1837 while accompanying Sir William Drummond Stewart.

depict at least some blunt-muzzle, relatively shorter haired dogs while he was

employed at Fort Union. These drawings are from Kurz’ journal. Lewis Garrard (Reference)

describes the use of dogs by Cheyenne Indians when moving a village location in 1847:

"Many of the largest dogs were packed with a small quantity of meat, or something

not easily injured. They look queerly, trotting industriously under their burdens;

and judging from a small stock of canine physiological information, not a little

of the wolf was in their composition." The image to below is modified from a drawing

made by Alfred Jacob Miller in 1837 while accompanying Sir William Drummond Stewart.

Dogs filled many roles in the Indian village, including guard, scavenger, beast of burden and source of food, however, the role of "Pet" was minor. During good times, dogs acted as scavengers to remove scraps and waste food. Dog was considered a delicacy and was not infrequently on the menu for feasts and other special occasions. Garrard describes preparation of dog in his journal.

When the village was on the move, dogs would be used to assist in hauling household

goods. Small travois or packs were fitted to dogs as shown in this  drawing by Kurz.

Dogs were also put to use pulling lodgepoles.

drawing by Kurz.

Dogs were also put to use pulling lodgepoles.

When winter travel was necessary, the dog sled was often used in place of horses. Dogs were often able to more easily move over deep snow in which a horse might be only be able to move with great difficulty and would soon be exhausted by the effort. Furthermore, with a sled, a couple of dogs could easily haul up to 150 pounds of goods and supplies, approximately three-quarters of the weight that could be packed by a horse or mule with solid footing.

There are two basic designs of dog sleds, the sledge and the cariole, both of which

look much like a toboggan but with a much higher front curl. The sledge was open,

whereas the cariole was enclosed in a frame covered with rawhide. The rawhide cover

on a cariole prevented snow from collecting on the sled and protected the contents

or passenger. Kurz in his journal

which

look much like a toboggan but with a much higher front curl. The sledge was open,

whereas the cariole was enclosed in a frame covered with rawhide. The rawhide cover

on a cariole prevented snow from collecting on the sled and protected the contents

or passenger. Kurz in his journal  describes carioles being used at Fort Union.

describes carioles being used at Fort Union.

If there were multiple sleds and men traveling together, the sleds would move as a “train.” One or two men in snowshoes would lead the way, beating a track which the dogs would naturally follow, as opposed to breaking their own trail. Under certain conditions of loose or soft snow, dogs might be unable to pull the sleds. In late winter or early spring, dog trains would often travel through the night when the snow was firm and frozen, and would rest during the days when soft, melting snows would easily tire the dogs.

Dogs used in the harness would need as much care and attention paid to their feet as would a pack or saddle horse. Here is a description of the use of “dog shoes.”

Dogs harnessed in a sled were still dogs, and given the proper distraction, could be as difficult to control as a horse as this story shows.

Frederick Ayer, in an article published in 1843 (reference) provides a general description of travel by dog sled:

“We traveled many whole days without seeing any living being, human or brute, except occasionally a red squirrel, or small bird. A short description of our mode of traveling, our habits, &c., may not be uninteresting to you, and may be, ere long, of service to you, (as I trust it will be) as missionaries in this country. I have before said that we used dogs, and a sledge, or train, to convey our baggage. It must be understood that there are no other roads than Indian foot paths; and of course, no public conveyance, resting place, or shelter, for the traveler, except some isolated trading houses, a hundred miles or more from each other. It is necessary therefore, for the traveler to take his bedding, provisions for himself and dogs, cooking utensils, leather to mend his shoes, thread to mend his clothes, axes to clear roads, chop wood, and cut branches for his bed &c.

Our usual course, on our late tour, was, to breakfast before daylight, and get in readiness to start on our way soon after. Our breakfast usually consisted of rice, or corn meal, boiled, and thickened with flour, and spiced with a little sugar. Our drink, cold water. In the morning we baked a bread cake, in a small frying pan. This served for our luncheon at noon. We never stopped during the day to cook, and generally ate our peice of bread even while walking.”

Ayer goes on to give a description of winter camping with the dog train, which can be found here.

In 1827 William Sublette and Moses "Black" Harris made an incredible journey of 1,200 miles on foot with a dog in the dead of winter, through deep snow, fierce storms and numbing cold. Each man carried a pack of dried buffalo meat, and the dog was loaded with a 50 pound pack of food. Often the men hiked through the night to avoid freezing. Somewhere along the trail, the dog-pack pulled free and it's contents were lost. Game was scarce, and gradually the men were reduced to starvation fare. The starving dog, weakened began to struggle into camp later and later each night. When they were still 200 miles from the nearest post, Harris suggested that they eat their dog. Sublette resisted at first, but was then persuaded. When finally the dog staggered into camp, the men were so weak that at first they were unable to kill the dog. Eventually the dog was killed and roasted over a fire. By morning the men were slightly revived and continued their trek.

In the winter of 1833-34 Prince Maximilian records (Reference) the use of dogs to pull sleds as follows: "These dogs, if they are not broken in, are quite unfit for the sledge; when, however, they are accustomed to the work, they draw a sledge over the snow more easily than the best horse. If the snow is froze, they run over it, where the horse sinks in, and they can hold out much longer. They can perform a journey of thirty miles in one day, and if they have rested an hour on the snow, and had some food, they are ready to set out again. A horse must have sufficient food, frequent rest, and a good watering place, and when it is once tired it cannot be induced to proceed. I have long been assured by some persons that they had made long journeys, for eight successive days, with dogs, during which time the animals did not taste any food."

Back to the Top

Back to Transportation